‘Factual through and through / absolutely approachable / flexible / warm / she knew what she wanted and she got what she wanted / progressive / very consistent / you felt valued / not afraid of male luminaries / very structured thinking / she was very well connected / she was very committed / she was an intelligent, art-loving, energetic woman / very caring, very family-conscious / she gave us wings / assertive / with a great love and a close relationship to things / who listened but at the same time had a very firm opinion / I already found her progressive / always in a good mood / perceived as a conservative person / she was really a personality that you don't really forget that easily’

You are now standing in front of the restoration workshops, the museum’s archive, and the wood shop. Until 1985, this is where the museum’s offices and administration were housed, since at the time the museum only consisted of Historical Villa Metzler and the buildings you see here.

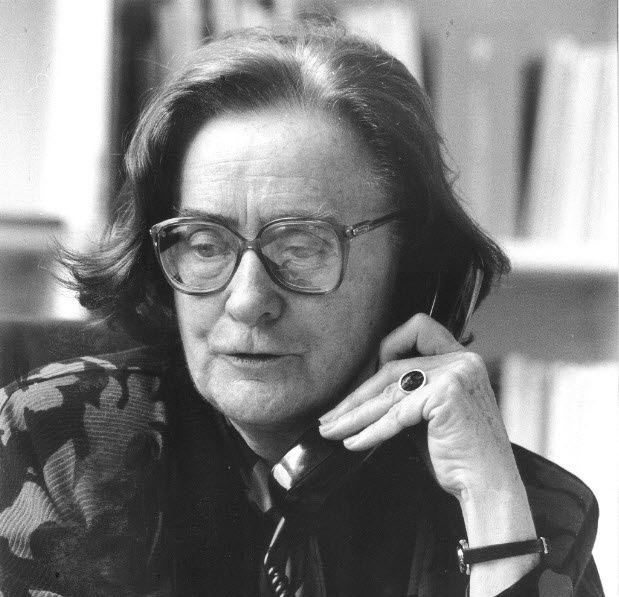

Born 1920 in Schlawe (Sławno in today’s Poland), Annaliese Ohm discovered her passion for art early on, and especially for applied art. In 1940, she began studying art history and archaeology, receiving her doctorate in 1951. She financed her studies by weaving straw into everyday objects and selling them. Her niece described Ohm as clever and imaginative. Many years followed in which she gained professional experience, working in a ministry of culture, in historical preservation, and a regional museum authority in Nordrhein-Westfalen. The tours and courses that she gave for schoolchildren, students, and interested people demonstrated early on how much enthusiasm she brought to the mediation of art and culture. Her educational trips to countries such as Sweden, England, Italy, Greece and Egypt and what was then Czechoslovakia (today the Czech Republic, the Slovak Republic, and parts of the Ukraine) made clear to Ohm, as she said in her own words: ‘how much help and consolation art offers’.

In 1964, Annaliese Ohm started working at Museum für Kunsthandwerk as the only scientific staff other than the then director. Two years later, she was appointed head of the department and curator for European applied arts. In 1974, she took on the position as the first female director of the museum. In the 1970s, men headed all the renowned museums in Frankfurt, except for Museum für Kunsthandwerk! Ivonne Rochau-Balinge, who later worked together with Ohm in the International Women’s Club of Frankfurt e. V., recalls:

‘In the 1970s and 1980s it really was unusual for a woman to lead a museum. But she had what it takes, with her assertiveness and her persistence. She also had a talent of being able to win people over with a certain charm. But she could also be really tough. You had to be, to stand your ground’.

When Ohm assumed her role as director, the museum had only a small staff. Gradually she managed to create the positions that were so desperately needed; in museum education, in the carpentry shop, restoration, and curation. Now she could carry out her vision for a professional reorganization of the museum on a level in keeping with its large collection.

Annaliese Ohm was particularly supportive of female museum staff, as her former colleague Dr. Eva-Maria Hanebutt-Benz remembers:

‘For example, she made it possible for me to travel through the US on a Fullbright scholarship, a four-week trip through American museums with a group of colleagues from Europe, and I was able to see all that, hear lectures, etc. That someone would make that possible for a younger colleague, a subordinate employee— This is where her very strong human interest gleamed through’.

Ohm’s progressive museum policy was also expressed in the way she filled leading positions in scholarly and academic fields, including art education, almost exclusively with women. She trained her staff to work independently and confidently and to contribute on their own.

Was her mentorship consciously focused on women, perhaps as a feminist approach? Even if we cannot answer this in retrospect, one thing is clear: Ohm wanted to enable women with families to have a career, something that is still not a given everywhere! She was attentive to women’s needs and was active in the International Women’s Club of Frankfurt e. V., holding the office of its president from 1988 to 1989.

Her courage, strength, and perseverance were rooted in her ‘often desperate search for home’ as she said herself. Ohm’s existential need to create a home for herself through art and culture possibly can be explained by her flight from Kolberg (Kołobrzeg in today’s Poland) in 1945. She understood that the museum could be just such a place—independent of its geographic location—a home for people.

In 1987, shortly after her retirement, Annaliese Ohm was awarded the Cross of Merit, First Class, of the Federal Republic of Germany for her outstanding achievement for contemporary applied arts and the realization of the new building. After over forty years of success in the art and culture scene, she entered a retirement home in Lübeck in 2000, where she died three years later.

Dr Sabine Runde describes the lasting influence of Annaliese Ohm’s period as museum director: ‘When you are encouraged, you learn a lot. This positive attitude alone brings you further. It helps you to have the courage to make decisions and to have confidence. Not only in yourself, but also in others’.

Sources:

Familie Bartels, obituary, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, March 5, 2003.

Margrit Bauer,recorded interview conducted at Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, September 1, 2021, from min. 26:52, from min. 26:58, from min. 27:00, from min. 27:02, from min. 27:16.

Roland Burgard, Museum für Kunsthandwerk Frankfurt am Main, Frankfurt am Main: Museum für Kunsthandwerk, 1988, p. 28.

Inge Burggraf,recorded interview conducted at Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, August 30, 2021, from min. 07:21, from 07:40.

H. D., ‘Zu wenig Platz für viele Schätze. CDU-Politiker informieren sich im Kunsthandwerksmuseum’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 48, March 1, 1978.

W. E., ‘Frankfurt Gesichter. Annaliese Ohm’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, December 11, 1982.

A. G.,‘Die Sammlungen fürs Publikum. Dr. Annaliese Ohm wird neue Direktorin des Kunsthandwerkmuseums,’ Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, no. 119, May 24, 1974, p. 52.

Antje and Johannes Hachmöller,recorded interview conducted at Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, September 22, 2021, from min. 08:50, from min. 08:56.

Eva-Maria Hanebutt-Benz,recorded interview conducted at Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, August 30, 2021, from min. 01:40, from min. 01:45, from min. 05:30, from min. 20:00, from min. 20:06, from min. 25:16, min. 25:30–25:35, min. 25:40–26:12, from min. 28:04, from min. 28:19, from min. 28:30, from min. 28:36, from min. 29:57, from min. 30:10.

International Women's Club Frankfurt e. V., obituary, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, March 2003.

Annaliese Ohm, farewell address, manuscript, May 20, 1987, p. 2.

Annaliese Ohm, curriculum vitae, Museum Archive.

Annaliese Ohm, curriculum vitae, employee file, preserved at Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt am Main, 1964.

Press and Communications Office of the City of Frankfurt,‘Bundesverdienstkreuz für Dr. Annaliese Ohm. Bürgermeister Dr. Hans-Jürgen Moog überreicht den Orden’, press release, November 11, 1987.

Press and Communications Office of the City of Frankfurt,‘Große Verdienste um das Deutsche Kunsthandwerk. Zum Abschied der Museumsdirektorin Dr. Annaliese Ohm’, press release, May 18, 1987.

Ivonne Rochau-Balinge,recorded interview conducted at Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, August 30, 2021, from min. 00:44, from min. 01:08, from min. 01:13, from min. 37:40, from min. 41:31.

Sabine Runde, conversation at Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, July 14, 2021.

Sabine Runde,recorded interview conducted at Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main, August 30, 2021, from min. 25:20, from min. 35:00.

to start the audio segment.

to start the audio segment.